IMMUNE-NURTURING BENEFITS

Successful management of cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) starts with an early diagnosis and requires ongoing support to ensure that infants and young children receive an appropriate elimination diet in order to reach their full potential. Nestlé Health Science is committed to helping you and your patients throughout the diagnosis and management journey.

1 - Starting the elimination diet

and food challenge

2 - Advise caregivers for

complementary feeding

3 - Monitor long-term growth

and development

4 - Periodically test for

tolerance

BREAST MILK IS THE GOLD STANDARD

FOR INFANTS WITH CMPA

Mothers of infants with CMPA should be supported to continue breastfeeding. Breast milk contains all the essential nutrients infants need in their first 6 months of life and should thereafter be complemented with a cow’s milk protein-free diet. In rare cases where infants react to cow’s milk transmitted through breast milk, mothers might have to eliminate cow’s milk proteins from their diet.

A clear improvement of CMPA symptoms is usually noticeable after the exclusion of cow’s milk protein in 2 to 4 weeks, and sometimes even earlier. It may be necessary for the mother to take daily calcium and vitamin D supplements while on a cow’s milk protein-free diet.1-3

To confirm or exclude the diagnosis, a controlled oral food challenge under medical supervision may be required.2 Learn more about food challenge here.

BREAST MILK NURTURE INFANTS' IMMUNE SYSTEMS

Infants with CMPA are at an increased risk of infections and future allergies.4-6 As breastfeeding has been shown to reduce the incidence of infections and future allergies, this provides yet another important reason to support mothers to breastfeed.7-11

These outcomes are attributed to diverse bioactive components present in breast milk, including human milk oligosaccharides (HMO).12 HMO are the third most abundant solid component of breast milk, and play an important immune-nurturing role.12

While there are over 200 of these structurally complex carbohydrates,12 two of them, 2’ Fucosyllactose (2’FL) and Lacto-N-(neo)tetraose (LNnT), account for more than 30% of HMO in breast milk.13

Several clinical studies reported the protective effect of breastfeeding

for infants, including a reduced incidence of:

SPECIALTY FORMULAS FOR CMPA

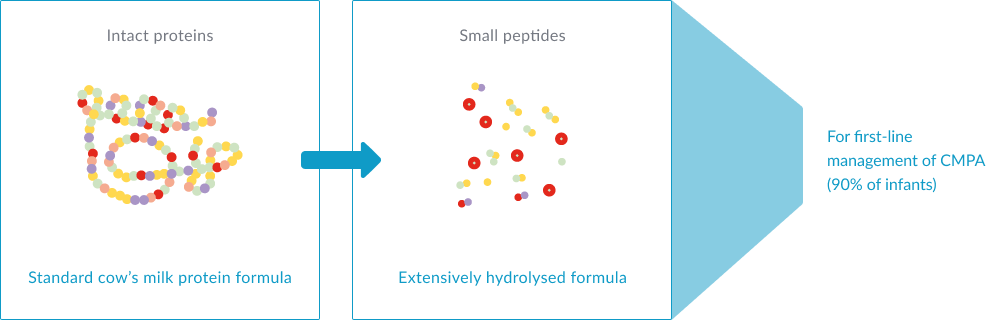

When exclusive breastfeeding is not feasible, specialty formulas clinically proven to be hypoallergenic for infants with CMPA are recommended.1-3,14 These formulas contain all the necessary nutrients to support growth and development.

These specialty formulas can be:

Extensively hydrolysed formulas (eHFs): prepared from cow’s milk protein which have been hydrolysed (amongst other processes) to break them down into peptides, so that they are hypoallergenic and are less likely to cause an allergic reaction. eHFs, like Althéra® HMO and Alfaré® HMO, are recommended for first-line management of infants with CMPA.1-3,14

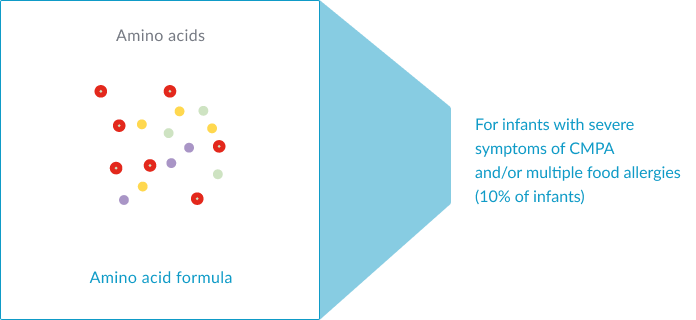

Amino acid-based formulas (AAFs): prepared from free amino acids. AAFs, such as Alfamino® HMO, are recommended in infants with severe symptoms of CMPA and/or multiple food allergies.1-3,14

Once an infant has eliminated cow’s milk protein from their diet with a specialty formula, CMPA symptoms typically resolve between 1-4 weeks, and sometimes sooner.2 To confirm or exclude the diagnosis, a controlled oral food challenge under medical supervision is often required. Learn more about food challenge here.

EXPERT CORNER: CMPA MANAGEMENT

In these videos, Professor Christophe Dupont provides an overview of CMPA and how to manage it effectively.

COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING AND CMPA

In the first six months of an infant’s life, exclusive breastfeeding is the preferred choice. In case breastfeeding is not possible for any reason, a special hypoallergenic formula for CMPA is recommended. Thereafter, it is time to introduce solid foods, as nutrient requirements increase.1-3,14

In infants with CMPA, whilst it is important to continue avoiding cow’s milk, other foods can be introduced just as it would be done with a non-allergic infant. There is no evidence that delaying the introduction of other potentially allergenic foods (e.g. wheat, soya, egg, fish, nuts…) will prevent the development of other food allergies. In fact, evidence is building that early rather than delayed introduction of these foods could be beneficial.15

A variety of different foods and flavours should be introduced into the weaning diet while still avoiding cow’s milk protein. During this time, specialty formula should still contribute a major part of an infant diet but it can also be used in recipes.

MONITORING LONG-TERM GROWTH IS ESSENTIALS

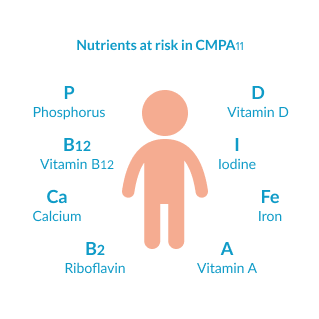

Elimination diets are necessary to prevent symptoms. However, they do increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies. In fact, several studies show how CMPA is linked to significantly lower growth in childhood if caregivers do not have professional dietetic support. It is therefore essential that caregivers are supported appropriately during this time. Nutrients at risk include calcium, vitamin D and iodine amongst others.16

WHEN AND HOW TO TEST FOR TOLERANCE

Half of all children with CMPA will outgrow it by 1-2 years of age, whilst the majority will outgrow it by 3 years of age, but it is difficult to predict when it will be achieved in each case.3,17 Non-IgE-mediated allergies tend to resolve more rapidly than IgE-mediated allergy or those with multiple food allergies.3

It is recommended to re-challenge children with CMPA every 6 to 12 months to assess whether they have developed tolerance to cow’s milk protein. Overly long dietary eliminations should be avoided as they might impair the quality of life of both the child and family, or increase the risk of impacting the child’s growth.2,3,14

Some guidelines recommend to start re-introduction with small amounts of milk in baked form (e.g. biscuits, cookies), as baking destroys a majority of epitopes causing the allergy. If the infant tolerates baked products well, introduction of products containing a larger amount of milk and/or in a less denatured form can be attempted.3 However, the practice differs between countries, and local recommendations about when and how to test for tolerance should be used.

Re-introduction may provoke allergic reactions and reappearance of symptoms. It should only be attempted with the guidance and under the supervision of a healthcare professional, as well as following local guidelines.

REAL-LIFE CASE STUDIES OF INFANTS WITH CMPA

Every infant is individual and the diversity of CMPA symptoms can make diagnosing and managing the condition particularly challenging. Here you will find several real-life case studies of infants with CMPA whose conditions have been successfully managed.

Dai, 1 months old

Constipation and inconsolable crying

Joey, 4 months old

Severe eczema particularly on the face

Harry, 5 months old

Colic and immediate

gastrointestinal symptoms after feeding

Oliver, 2 weeks old

Constipation and unsettled

Vivian, 6 months old

Pale, lethargic, and dehydrated

with a weak cry

Emil, 7 months old

Symptoms of eczema and reflux

OUR RANGE OF TAILOR-MADE NUTRITIONAL SOLUTIONS

Nestlé Health Science has a range of nutritional solutions that are tailor-made to meet the specific needs of infants with CMPA. Our formulas are nutritionally complete to support normal growth and development in infants, with the addition of HMO* to support growing immune systems.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

VISIT OUR RESOURCE CENTRE

* Structurally identical Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMO) are not sourced from human milk

REFERENCES:

-

Nowak-Węgrzyn A, et al. Evaluation of Hypoallergenicity of a New, Amino Acid–Based Formula. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2015;54:264–272.

-

Nowak-Wegrzyn A, et al. Confirmed Hypoallergenicity of a Novel Whey-Based Extensively Hydrolyzed Infant Formula Containing Two Human Milk Oligosaccharides. Nutrients 2019;11(7):E1447.

-

Cekola P, et al. Clinical use and safety of an amino acid-based infant formula in a real world setting. Abstract presented at NASPGHAN. Chicago, IL, USA, October 2019.

-

Koletzko S, et al. Diagnostic Approach and Management of Cow’s-Milk Protein Allergy in Infants and Children: ESPGHAN GI Committee Practical Guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;55(2):221-229.

-

Luyt D, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2014;44(5):642-672.

-

Muraro A, et al. EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy 2014;69(8):1008–1025.

-

Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides: Every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology 2012;22(9):1147-1162.

-

Donovan SM and Comstock SS. Human Milk Oligosaccharides Influence Neonatal Mucosal and Systemic Immunity. Ann Nutr Metab 2016;69(suppl 2):42-51.

-

Nestlé Health Science, data on file. CINNAMON study.

-

Vandenplas Y, et al. Growth, tolerance and safety of an extensively hydrolysed formula containing two human milk oligosaccharides in infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Abstract presented at PAAM. Florence, Italy, October 19, 2019.

-

Puccio G, et al. Effects of Infant Formula With Human Milk Oligosaccharides on Growth and Morbidity: A Randomized Multicenter Trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64(4):624-631.

-

Heine RG, et al. Lactose intolerance and gastrointestinal cow’s milk allergy in infants and children – common misconceptions revisited. World Allergy Organ J 2017;10(1):41.

-

Delplanque B, et al. Lipid Quality in Infant Nutrition: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;61(1):8-17.

-

Bach AC, et al. Medium-chain triglycerides : an update. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;36(5):950-962.

-

Kennedy K, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial of a synthetic triacylglycerol in formula-fed term infants: effects on stool biochemistry, stool characteristics, and bone mineralization. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70(5):920-927.

-

Koletzko B. Human milk lipids. Ann Nutr Metab 2016;69(suppl 2):28-40.

-

Mazzocchi A, et al. The Role of Lipids in Human Milk and Infant Formulae. Nutrients 2018;10(5):E567.

-

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Pediatrics 1976;57:278-285.

-

Nestlé Health Science, data on file. Alfamino® product composition.

-

Corkins M, et al. Assessment of Growth of Infants Fed an Amino Acid-Based Formula. Clin Med Insights Pediatr 2016;10:3–9.

-

Vandenplas Y, et al. Growth in infants with cow’s milk protein allergy fed an amino acid-based formula. Abstract N-O-013 presented at ESPGHAN, 2019. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;68(Suppl 1).

-

Nestlé Health Science, data on file. Alfamino® versus Neocate® competitive benchmarking test.

-

Host A and Halken S. Cow's milk allergy: where have we come from and where are we going? Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2014;14(1):2-8.

-

Azad MB, et al. Infant gut microbiota and food sensitization: associations in the first year of life. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45(3):632-643.

-

West CE, et al. The gut microbiota and its role in the development of allergic disease: a wider perspective Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45(1):43–53.

-

Thompson-Chagoyan OC, et al. Faecal Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels in Faeces from Infants with Cow‘s Milk Protein Allergy Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2011;156(3):325–332.

-

Chin AM, et al. Morphogenesis and maturation of the embryonic and postnatal intestine. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017;66:81-93.

-

Tanaka M and Nakayama J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life Allergol Int 2017;66(4):515-522.

-

Newburg DS and Walker WA. Protection of the Neonate by the Innate Immune System of Developing Gut and of Human Milk. Pediatr Res 2007;61(1):2-8.

-

Woicka-Kolejwa K, et al. Food allergy is associated with recurrent respiratory tract infections during childhood. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2016;33(2):109-113.

-

Juntti H, et al. Cow’s Milk Allergy is Associated with Recurrent Otitis Media During Childhood. Acta Otolaryngol 1999;119(8):867-873.

-

Tikkanen S, et al. Status of children with cow’s milk allergy in infancy by 10 years of Age. Acta Paediatr 2000; 89(10):1174-1180.

-

Jalonen T. Identical intestinal permeability changes in children with different clinical manifestations of cow’s milk allergy. J allergy Clin Immunol 1991;88(5):737-742.

-

Crittenden RG and Bennett LE. Cow’s Milk Allergy: A Complex Disorder. J Am Coll Nutr 2005;24(6suppl):582S–591S.